Salam…

Ini adalah tutorial pertama yang aku buat. Tujuannya hanyalah untuk berkongsi cara-cara untuk membuat printing di atas fabrik secara d.i.y menggunakan barang-barang yang mudah dan tak perlukan sebarang kemahiran khusus seperti untuk expose design atas printing block.

Dengan kaedah yang aku sering lakukan ini, sesiapa sahaja boleh untuk mencuba melakukannya, dengan menggunakan skil di tahap minima. Oleh itu, kita mulakan acara.

Peralatan

Peralatan yang korang perlu ada ialah :

- Pisau pemotong kertas.

- Pembaris (jika korang perlu untuk membuat garisan yang tepat. biasanya aku tidak akan menggunakan pembaris kerana aku lebih suka jika hasilnya menampakkan sedikit human-touch)

- Pensel mekanikal (aku syorkan pensel mekanikal kerana diameter led nya sama. Pensel kayu akan menghasilkan ketebalan berbeza selepas digunakan untuk tempah yang panjang dan ini akan mengganggu design yang ditrace.

- Cat Acrylic (cat ini boleh didapati di kebanyakan art-shop. yang paling murah yang aku jumpa adalah jenama College Rm11.90)

- Sticker paper (ini boleh korang jumpa di Popular Book Store. Harga Rm4.00 untuk 10 keping kertas sticker bersaiz A4)

- Putik Kapas (atau alat lain yang korang rasakan mudah untuk distribute cat dengan rata dan berkesan. Cotton buds works fine for me.)

- Design (korang boleh menggunakan komputer untuk cetak design di atas kertas sticker untuk kemudahan, tapi di sini aku nak tunjuk teknik tracing yang aku sering gunakan).

- Pengering Rambut (untuk mempercepatkan proses pengeringan)

- Seterika (untuk melekat stensil ke atas material)

- Permanent Marker Pen (untuk tujuan touch up)

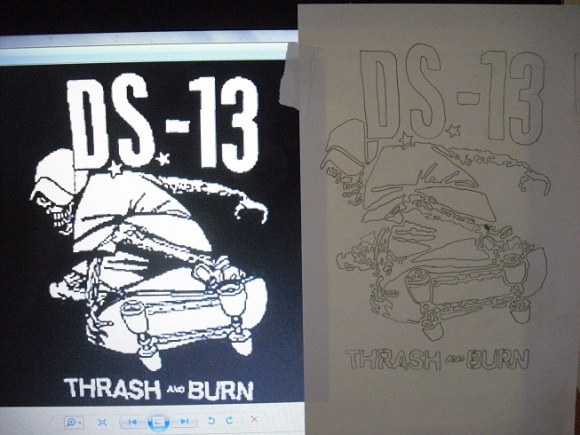

Design yang akan aku gunakan kali ini adalah dari DS-13 Thrash and Burn. Korang boleh memilih apa sahaja design yang korang mahu, tapi untuk yang baru pertama kali mencuba, dinasihatkan untuk bermula dengan design yang mudah dan tidak kompleks butirannya. Design yang aku guna ini agak berisiko kerana butirannya agak kompleks sedikit. Risikonya adalah jika korang tak biasa dengan detail, print-outnya akan jadi agak mengecewakan, dan bakal merosakkan material yang korang print tadi, kerana Acrylic tak boleh dipadam seperti cat air, ianya akan kekal di atas material tersebut, lebih-lebih lagi fabrik.

Meletakkan design.

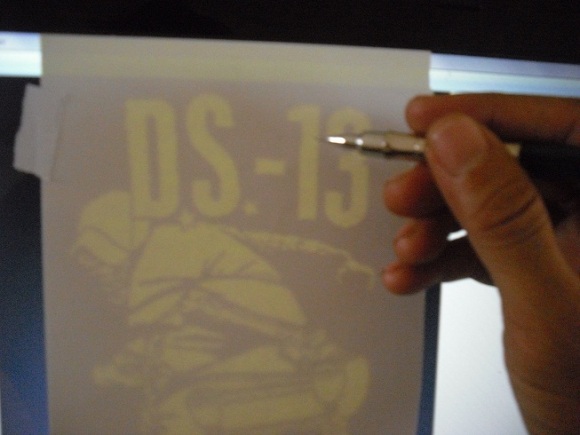

Aku menggunakan teknik tracing, bermaksud menindihkan kertas sticker di atas design, dan trace garisan menggunakan pensel/pen/arang/kapur atau apa sahaja. Pensel lebih baik kerana sebarang kesilapan boleh dipadam.

Namun begitu, aku akan trace terus di atas skrin komputer/laptop, kerana ini memberi pencahayaan yang cukup untuk tujuan tracing, dan aku tak perlu untuk mengeluarkan modal ekstra bagi tujuan printing. Teknik ini tidak mempunyai sebarang nama, jadi untuk tujuan tutorial, aku namakan tekni ini screen-tracing.

Untuk teknik ini, korang perlu tumpukan perhatian pada warna hitam/warna gelap yang terdapat pada design kerana ini memudahkan kerja. Jika menumpukan pada warna yang cerah, kebiasaannya, garis yang dihasilkan akan menjadi sedikit tidak stabil. ini akan mencacatkan design.

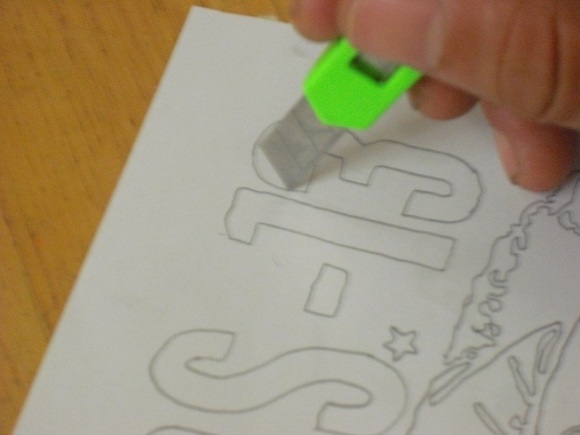

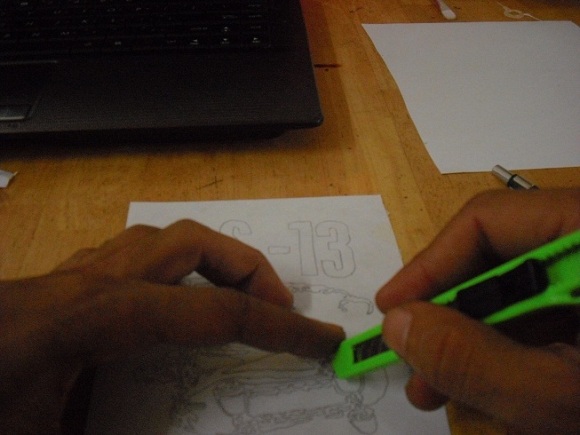

Memotong Design (Stensil)

Terpulang kepada kemahuan korang untuk design yang terhasil, design harus dipotong dengan perlahan dan teliti. Untuk design ini, aku ingin meletakkannya di atas material berwarna hitam dan design berwarna putih, sama seperti design sebenar. Jadi waktu memotong nanti aku akan membuang bahagian design yang berwarna putih. oleh itu untuk membuang mana-mana bahagian, korang harus meneliti semula design asal supaya tidak tersilap. Ingat, sebarang kesilapan tak mudah untuk dibetulkan.

Tidak ada sebarang teknik khusus untuk memotong design (yang pasti jangan mencuba teknik memotong daging, kertas ini delicate), namun ada beberapa aspek yang harus diperhatikan:

- Pisau harus dalam keadaan sempurna/tajam/tak berkarat.

- Mata pisau harus dikeluarkan sedikit sahaja..

- Potong perlahan, cuba untuk memotong dengan sebanyak masa yang ada. Jangan gopoh.

- Gunakan hujung mata pisau sahaja kerana kita tak mahu design itu terlebih potong dan dengan menggunakan hujung mata pisau, korang akan dapat lebih kawalan terhadap pemotongan itu nanti.

- dengan kekuatan dan tenaga manusia biasa, mata pisau akan menjadi lebih dalam di hujung tarikan, jadi apa yang korang boleh buat jika mata pisau terasa berat dan tidak lagi boleh ditarik, hanya angkat mata pisau ke atas sedikit, dan teruskan pemotongan. Jangan cuba untuk memotong dengan terlalu panjang, cukup jika tarikannya pendek kerana lebih kawalan.

- Korang juga boleh cuba teknik menolak pisau dengan jari tangan kiri, supaya tangan kanan hanya difokuskan untuk mengemudi mata pisau. Ini membantu kepada ketepatan potongan.

- Untuk memotong garis yang terlalu pendek, korang hanya perlu menekan mata pisau tegak kebawah, sehingga ia memotong keseluruhan garis tersebut.

Meletakkan design

Setelah kertas sticker tadi selesai dipotong, buang dahulu bahagian yang mahu dicetak. Ini akan menghasilkan stensil dari sticker tadi. Kemudian kopek dengan cermat. Ini adalah salah satu daripada bahagian penting yang perlu diambil perhatian. Perlu berhati-hati untuk tidak merosakkan stensil tersebut sebelum meletakkannya di atas material yang mahu di print.

Stensil tersebut harus diseterika supaya ia melekat dengan rapi dan mengelak dari berlaku sebarang lelehan atau spilling. (spilling terjadi apabila garis design tidak melekat dengan kuat dan menyebabkan cat masuk ke bawah bahagian yang ditutup sticker. Ia juga boleh terjadi apabila cat itu masuk ke bahagian serat benang yang terlalu halus untuk ditutup dengan sticker, tetapi kesan spilling ini minor dan boleh di touch-up.)

Memasukkan Warna

Setelah siap meletakkan stensil sekarang ia telah sedia untuk diwarnakan (atau di print).Keluarkan sedikit cat Acrylic, letak di atas pallet. Aku hanya gunakan alas kertas yang ada untuk letakkan cat itu, kerana tidak mahu membazir masa membasuh pallet. Ambil putik kapas dan putarkan dicat tersebut untuk menyalut dan menyerap cat ke putik kapas.

Kemudian terus sapukan ke atas stensil tadi. Prosesnya harus dilakukan sebanyak 3 lapisan atau lebih, sehingga korang puas hati. Jangan cuba meletakkan cat terlalu banyak kerana ingin mempercepat/memendekkan proses. Pastikan cat tersebut telah kering sepenuhnya di antara setiap lapisan. Gunakan pengering rambut untuk itu.

Lapisan ketiga akan membuatkan design tersebut lebih terang dan rata, maaf tidak ada gambar diambil untuk itu.

Hasil

Setelah kering design tersebut, sticker dah boleh ditanggalkan. Tanggalkan dengan berhati-hati kerana tidak mahu iya tertinggal dan melekat pada design tanpa korang sedar. Sentiasa refer pada design asal sewaktu menanggalkan stensil. Kebiasaannya stensil yang telah digunakan tersebut harus dibuang, lebih-lebih lagi jika ada design yang banyak garis-garis halus. Design yang lebih besar misalnya, mungkin boleh digunakan semula jika ditanggalkan dalam keadaan yang sempurna (contohnya logo DOOM)

Jangan risau jika korang ada nampak sebarang spilling berlaku. Langkah terakhir ini adalah untuk touch-up design supaya jadi lebih sempurna. Touch up dengan sebarang alat yang korang rasa sesuai, aku lebih gemar touch up dengan menggunakan permanent marker pen.

Setelah siap touch up, maka siaplah kerja korang. Design yang terhasil mungkin ada kekurangan sedikit dari grafik asal, tapi sekurang-kurangnya korang dah berjaya menghasilkan sesuatu dengan sendiri.

Korang boleh gunakan teknik ini untuk menghasilkan patches, atau lebih menarik lagi jika korang print terus ke atas jaket, atau seluar korang. Boleh juga di gunakan diatas beg. Untuk tutorial ini aku gunakan beg, kerana beg aku terlalu kosong dan bosan.

Selesai, D.I.Y or D.I.E